Saturday, September 29, 2012

memorial

At John Clarke's memorial service in the dell; a muggy, late-summer afternoon. Two hundred people there. One comment: "Whenever you were in his presence, you were always better for it." And it was true. Always. He was a remarkable person. As is Elizabeth, with her remarkable eulogy.

Tuesday, September 25, 2012

Sunday, September 23, 2012

Saturday, September 22, 2012

Friday, September 21, 2012

Thursday, September 20, 2012

Wednesday, September 19, 2012

Tuesday, September 18, 2012

Monday, September 17, 2012

Sunday, September 16, 2012

Saturday, September 15, 2012

Friday, September 14, 2012

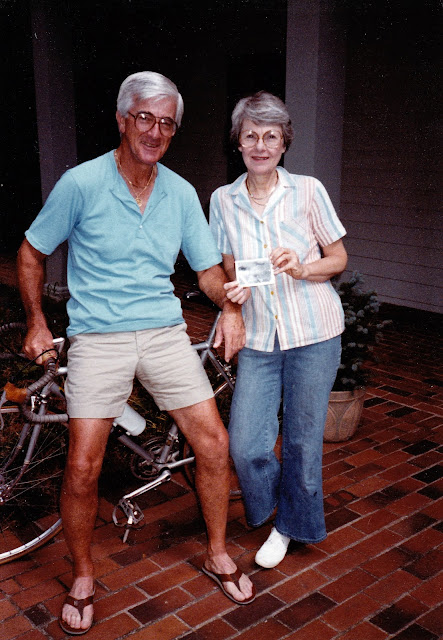

you have no idea . . .

Why they're laughing, or, what's in the pic your mom's holding. That's your bike. The early-mid '70s.

Thursday, September 13, 2012

Wednesday, September 12, 2012

Tuesday, September 11, 2012

Monday, September 10, 2012

Sunday, September 9, 2012

eulogy for sah

Eulogy for Stewart Albert Hurlburt

By Steven R. Hurlburt

September 6, 2012

Arlington Memorial Park

A Thursday afternoon

Arlington Memorial Park

A Thursday afternoon

Thanks to everyone for coming, for paying attention

to my dad. If he was here he would

probably be a little embarrassed and self-conscious of the whole affair – all

this fuss – just for him. It’s not that

he wasn’t gregarious or didn’t get along with people; he did. But he was a private, conservative person and

wasn’t much for ostentation or big shows of emotion.

This day, two years ago, he had his first heart

attack; it was a big one, and it almost killed him. Word spread about his condition, as it normally

would after someone has a heart attack; friends and relatives from Atlanta and

Highlands called to see how he was doing and to wish him well.

A couple weeks later, we were having BLT’s for

lunch. He had stabilized, was out of the

hospital and feeling as close to normal as he would ever feel again. We were talking (though I don’t remember what

about), and I could tell he was feeling agitated, something was off. I

asked what was up and he said the news of his situation was “all over the place.” I said, well, OK . . . that’s normal. He looked at me a bit askance and said he

didn’t want people to think that he and my mother were, and I quote, “big shots or something. We’re just not comfortable with that.”

______________

My dad was a Yankee, born in East Orange, New Jersey

to favorable circumstances. He was the third

son of, on the male side, solid British stock that had lived in the northeast

since the 1600’s, and on the female side, a striking woman from the plains of

Minnesota. His father was an engineer

and inventor: he helped construct,

design and install infrastructure in places as varied (and at the time, exotic)

as Bermuda and the Panama Canal; he built a wooden skiff in his back yard with

his three sons (dad being the youngest) which they kept at the Jersey shore; and

from my only visit to his house, I have the dreamy memory of the motorized

miniature planes and boats granddad created cutting through air and water, and

the cool hand-held metal boxes with buttons and switches that controlled them. It was magic.

And it was way better than Xbox.

My dad grew up lucky, as did I. His father would take him and the boys

camping on a friend’s farm out in the Jersey wilds where he learned how to use

a knife and how to tie knots whose prefixes were sometimes obvious from their

looks: square, figure eight; other times mysterious: like the granny and the half hitch. He spent summers in Seaside Heights, scooping

ice cream on the boardwalk, lifeguarding on the beach and adventuring in the

skiff with his brothers. He loved the

water – being on it or in it – and he loved sports (he wrestled and played

lacrosse). He played football at Rutgers

where he suffered a knee injury that affected him throughout his life.

My dad was a Marine.

He graduated Rutgers on a Sunday and on Monday morning he enlisted in

the Corps. He wouldn’t tell you this but

in his first training class he was ranked 14th out of the 252 other officer

candidates; in his second, at Quantico, he was 6th in a class of 250. He was then assigned duty at Shangri-La (now

Camp David), where he was one of three officers charged with the security of

the President and other dignitaries.

After that, upon reaching the rank of Captain, he was attached to the

light cruiser U.S.S. Vicksburg as Commanding Officer of the Marine detachment

on board. He saw action in the seas

surrounding Iwo Jima and Okinawa, and the Vicksburg was one of the first U.S. ships to enter Tokyo Harbor to oversee

the Japanese surrender. He would occasionally

share his memories of these best-of-times, but only if prompted. He had simply done his duty. After four years of service, he resigned his

commission and entered Harvard Business School. He graduated two years later

and moved to Atlanta for work.

My dad was a Southerner. Growing up in New Jersey, I guess you could

say he started out as a Southern atheist – he just didn’t know any better. He probably turned agnostic when he moved to

Atlanta to work, then became a true convert when he met my mom – as southern as

they come. From there he never looked

back. They were introduced at the Druid

Hills Country Club (back when it was actually in the country), romanced for a

year and married in 1949. Kids soon

followed; first me, then my brother Mark two years later.

The years went by as a wholesome, but not entirely

trouble-free, fifties and sixties cliché.

My dad was trim, dark, handsome, a corporate man, a snappy dresser, a

family man genuinely devoted to his wife and kids and church. He

gave up smoking; he drank little. He

kicked the soccer ball around with us, and took us to The Varsity and Georgia

Tech football games. He built a tree

house in the back yard. He did a hundred

thousand things for Mark and mom and me I can’t even remember. He was somehow always there. Semper fidelis.

I remember being on vacation in Sea Island; I was

maybe five or six years old. It was our

first afternoon and the family was walking around, inspecting the pool, the

beach, whatever. I happened to step off

the sidewalk into a nest of sand spurs and I’m sure I screamed and was about to

tumble to the ground because my feet were covered with them and I just couldn’t

stand up. I was about to crumple into

the spur infested ground, and there he was, like Superman, effortlessly lifting

me up in his arms of steel.

He refereed high school football games at Grady

Stadium, hardly a mile from where I now live.

At one point he bought a motorcycle. He played golf some weekends, and when he

wasn’t doing that he cut the grass, raked the leaves, fixed the roof, kept the

house shipshape. The massive tool bench

he inherited from his father – that his father built – was always covered with

one project or another but was never a mess.

Dad loved tools; there was nothing better than a well made implement

designed to do a specific job well. He

could fix anything. My brother and I

observed his habits, his attention to detail, his affection for symmetry and

order, and when we could, helped out. Meanwhile,

my mother, the house manager, ferried us to school and little league, made sure

we had decent clothes and did our homework.

She fed us and tucked us into bed and nursed us when we were sick. And, she had an organic garden in the back

yard, way before it was cool.

In my early teens, I remember dad coming home from

work one day very discouraged. He

usually didn’t talk about his job, but this time was different. He’d undergone some kind of standard

psychological profile testing, designed to determine his strengths and

weaknesses in the corporate arena. What

he couldn’t understand was the answer to the question: “In performing your job, do you trust your

fellow workers a) completely, b) somewhat, or c) not very much. He, of course,

answered “completely,” because he expected his colleagues’ standards of honor,

truth and doing the right thing to be the same as his, which he didn’t view as

elevated, just normal. That the correct

answer was “somewhat” sent him reeling.

It did not compute.

My dad was a Christian in the best sense of the

word. The Catholic writer Andrew Sullivan

sums it up this way: “A Christian is not

a Christian simply because he agrees to conform his life to some set of eternal

principles or dogmas; or because at one particular moment in his life, he

experienced a rupture and changed himself entirely. He is a Christian primarily because he acts

like one. He loves and forgives; he

listens and prays; he contemplates and befriends; his faith and his life fuse

into an unselfconscious unity that both affirms a tradition of moral life and .

. . makes it his own.” Dad was kind in spirit and had a generous

heart; he had a keen sense of honor and commitment and idealism and of doing

the right thing well.

He led by example, not by wagging his finger, and in

that way he was also conservative in the best sense of that word. He was suspicious of change and had an

appreciation of the inherited traditions and wisdom of the past. He wanted to

conserve and preserve nature and the environment. His life was lived in modest pragmatism. He believed in live and let live. He didn’t want to remake the world in his own

image. He believed in individual liberty

and personal responsibility. He was not

a joiner of fundamentalist causes. He

practiced charity to all.

When I went off to college (and then beyond), my dad

was fortunate enough to be able to retire early. He painted a bit – you can see a couple of

his pieces on your program – and I feel this silent, solitary art form suited

him; I wish he would have done more. He

and my mom spent time at their house in Garden City Beach. They became grandparents. They built their house in Highlands. He played golf and won a club

championship. He even came to see his

43-year-old son’s rock band play a gig in some crappy, smoky bar, which was

definitely beyond the call of duty. He

buried his younger son.

____________

My dad was optimistic, and for the most part, life

treated him well; but as it does with all of us, it eventually undid him. It started with the death of my brother ten

years ago. It continued when he had a

bad fall – breaking his nose and hurting his hip on a family cruise a couple

years later. Then the heart attack, then

congestive heart failure, then another heart attack. Slowly the strong, generous heart that had

served him and others so well was giving in to that Bastard Death, his arms of

steel wasting away to nothingness, and he couldn’t quite, or didn’t want to

grasp that. Finally, however, he did. “There

isn’t any place I can go to get rest,” he said to me one night, exhausted. And then, “No sense in you wasting your time

here, Steve.” And then, “I thought I

could get out from under all this . . . but I can’t.” It was one of the few times he told me he

couldn’t do something, and he faced that Bastard Death with way more grace and

courage than it deserves.

Eventually he was reduced to spending much of his

time in a chair in his bedroom. But even

then one of his youthful enthusiams was his comfort. Through the years he’d collected dozens of

pocket knives of all shapes and sizes. (“Hurlburt

men have always carried a pocket knife,” he once told me.) They were something

he appreciated: a well made instrument designed to do a job well. He loved the sharpened edge, the compact

design, the satisfying snap-and-click sound as he pushed the blade back into

the body of the knife. I used to hate

the fact that he would sit in that chair and open mounds of junk mail, all

wanting him to give money for the latest disaster du jour or to buy something from the Scooter Store or to stock up

on something called Grout Bully. But one

day as I sat there watching him open all that crap with the always-sharp edge

of one of his favorite knives, I realized it wasn’t the crap he was interested

in. It was the blade – that ancient, primitive thing. The blade wasn’t ostentatious or frivilous;

it was something you could count on. It

wasn’t trendy or flashy or transitory; it was something, actually, that was

very conservative, like him. It was the

sharpness of the knife, the soul of that blade, the crease in the envelope yielding

easily to the honed edge, the precise engineered click and snap of an

instrument from our ancient past – one made well and doing its job well – that gave him something to look forward to.

Although he might give me that “askance” look again

if he were here, I don’t think I’m exaggerating when I say that my dad was a

great man; he was a good, kind soul; not self-seeking or self-aggrandizing; he

was generous to a fault. And in spite of

all of the inevitable failings wrapped up in our humanity, as much as it was

humanly possible, he really was a man who, as the writer of Philippians says,

was true, honest, just, pure, lovely, of good repute, virtuous and praiseworthy. He was a man of high character, and we are

all a bit diminished now that he’s no longer with us.

Those are some of my thoughts about my father. If you would, I’d like to take just another

minute to read something else, something written by a man who’s not here

today. It’s a letter my brother wrote to

my dad almost 20 years ago when he was 38-years-old.

It’s dated June 20, 1993, and it reads:

Dear Dad--

As we get older we tend to forget a lot of things,

but I remember so many things that make you a great Dad and I want to say

thanks.

Thanks for the little car you got me when I cut the

end of my finger off in Dayton.

(He must have been about four year old then.)

Thanks for all the Christmas eves you stayed up

putting toys together for Steve and me.

Thanks for the time you took carving me a wooden

knife. I wish I still had one of

those.

Thanks for the skateboard you made me from that

piece of kitchen countertop.

Thanks for my first bike, my first pocket knife, my

first .22, my first hunting trip.

Thanks for turning me loose at the beach with the

john boat.

Thanks for the mini-bike you got me that must have

been a large problem with mom.

Thanks for my first motorcycle.

Thanks for still loving me during my teen years --

boy was I stupid.

Thanks for your advice over the years even though I

seldom took it—big mistake on my part.

Bottom line -- thanks for being a great dad all

these years. Love you pops.

Mark

p.s. Happy Father’s day

he's gone . . . cont'd

You ride alone, beneath the overcast, and arrive at

H.M. Patterson & Sons funeral home in Sandy Springs around nine to get

everything set up. You and Sandie were

there last week, after Stew had become bedbound. You’d met the Funeral Director, a

Capote-esque character with a Southern, almost-lispy speech pattern direct from

central casting, and “made arrangements.”

You choose the casket, the lining; you decide on pallbearers and are

cautioned by the FD not to use oldsters as pall bearers because the casket is

damn heavy and they might slip or fall and break a hip. One of the arrangements you wanted was a

Marine Guard at the graveside to blow “Taps.”

Months ago you’d called the local Marines office, the national office,

and a few other dead ends and wound up with nothing. You couldn’t find the right person to make it

happen, and you let it go. One of the

first questions the FD asked was if your dad was in the service, and if so, did

you want a Marine Guard at the funeral, and if you did, well he would

arrange it! Awesome. All you needed was your dad’s honorable

discharge papers. Where those are you

have no idea but after a day or two of tearing his office apart, they were

found.

The A/V people are already there erecting the

screen for the slide show. Introductions

and condolences from the guy who’s going to handle the service. The minister my mother wanted to officiate

shows up, pleasant and nice. Rebecca

sets up the computer for the slide show.

As you peruse the program again you see two more screw-ups: one of the

people giving a remembrance is named Bill Pike (not Joe, like the

program says), and you forgot to include a line for the slideshow. Jesus.

Around ten o’clock people start arriving for the

visitation. The casket is closed, draped

with a huge American flag, flanked by flowers.

You get to spend about thirty seconds with each person there; time’s

moving, fast. Before you’re

ready, the visitation room empties of guests and it’s just the family. The minister says a brief prayer; you’re

ushered into the hallway and then a short walk to the chapel. The program reads:

Prelude

Processional: “The Solid

Rock”

Greeting

“Because He Lives”: Jim

Bell, Lloyd Hess

Remembrances: Jane

Gouldman, Jenny Hurlburt, Joe Pike

Eulogy: Steven R.

Hurlburt

Meditation: Rev. Art

Wilder

“Brokedown Palace”:

Steven R. Hurlburt,

Rebecca Hurlburt, Jenny Hurlburt

Benediction

Recessional: “Joyful,

joyful We Adore Thee”

___________

Pall bearers: Phillip

Causey, Jim Gash, John Gouldman,

Ethan Hurlburt, Steven R.

Hurlburt, Rick Yost

You’re seated and the casket is wheeled in, almost

completely covered with Old Glory. It is

surrounded by flowers. A cross of white

flowers from my mother’s bridge group hangs on the wall behind it. Time speeds faster, faster. The minister prays, the singer sings with

that deep, pleasing, polished, old school Protestant voice. Jane’s remembrance is of your parents’ first

date; Jenny’s is of her granddad, the storyteller and Bill’s is one of deep

respect: dad as golfer, stand-up guy, a man’s man. Your hands are sweating like mad; you’re

emptying the box of Kleenex beside you, not dabbing tears away, but wiping the

sweat from your hands every few seconds.

How are you supposed to play guitar with soaked hands?

The slideshow, which we decided to put after the

remembrances and which is ten minutes long seems over in a flash. Now it’s your turn.

You walk up to the podium in time suspended. Your hands sweat. You look at the words you’ve written and

suddenly English becomes a foreign language.

You start to speak (you’ve rehearsed this, read it out loud, perfectly,

dozens of times) and you have marbles in your throat. You’re not choked up, you’ve just forgotten

how to enunciate words properly. You

hear every word critically. Gee, did I

just pronounce that word that way.

What the hell is going on? You

just plow ahead and hope for the best.

Overall, you had a few long compose-yourself pauses, but didn’t choke

up. You were OK.

Then the minister did Baptist standard-issue: he’s

in a better place paved with streets of gold and all his questions about life

are now answered and he suffered in this life so he could be really happy in

the next, etc. You don’t realize how

hollow that all sounds until someone’s saying it to your face at your father’s

funeral.

You and your daughters get up to do your song. The sweat’s still oozing from your hands and

apparently you’ve forgotten how to play a simple E chord. God, what is wrong with you. You’ve played the song a hundred times, and

now . . .? This is the first time you

and your daughters have sung together in public. They rally you and you all do a respectable

version. As they say, there wasn’t a dry

eye in the house.

The benediction and recessional and it’s over. Over.

It seemed to take no time at all.

Your hands aren’t sweating any more.

The casket is wheeled out to the hearse. The six of you load it in. Your mother rides with you in your car. The funeral caravan leaves slowly, the hearse

never going more than 25 miles an hour.

The motorcycle cops stop/direct traffic.

At an intersection one cop pulls over, gets off his bike, halts the

traffic and salutes as you go by. You

salute back. You and your mother say few

words, but she did say you and everyone else involved did well for your father.

You enter Arlington Memorial Park, where your

brother’s buried. The first thing you

see on entering is a huge, over-the-top mausoleum with the name CARLOS on

it. It’s not Louis XIV, but it is, well

. . . “That’s the worst thing I’ve ever

seen,” she says.

You drive by a thousand graves all with the

gaudiest, cheesiest, cheapest plastic flowers sprouting above them. Whoever thought that this was the way a

cemetery should present itself should be shot.

Seriously. “Now that’s the

worst thing I’ve ever seen,” your mom says.

With conviction.

But as you round a corner in the gently undulating hills,

the pines stretching tall and narrow in the grey sky, off to your left, a

hundred yards away, you see the gravesite set-up: the tent, the chairs . . .

and a space behind them, nine Marines in dress blues – eight men and one woman –

lined up at parade rest, and two others at the entrance to the

gravesite standing at attention awaiting your dad, and you instantly break into

tears and say reverently, involuntarily: “That’s awesome.” And your mother echoes: “That really is

awesome.” And it really, really is. You drive as slowly as you can to take it in

because all this respect and tradition and preparation is because of him, your

dad, what he did and how he served his country sixty years ago,

beginning the day after he graduated college, and you know you’ll never see

anything like it again. Ever. Semper fucking fi, Marine.

You glue your eyes to the spectacle before you; it’s a dream, and dreamlike, it will evaporate before you know it. You labor to take it all in and remember, remember . . . You round a corner and it’s out of sight for a bit; you round another corner, this time almost to the gravesite, and it’s still there, all of it. You get out of the car and mill around for a bit. Everyone’s crying as they look at the magnificent sight of the Marines, some of them surely the same age as your dad, when he was in the Corps. You and the other pallbearers line up at the back of the hearse. Suddenly, your dad’s brother-in-law Bob (Jane’s husband) joins us. He’s an “oldster” – just turned eighty – and in following the FD’s advice (yet another of your many oversights and mistakes in this whole process) you didn’t have him as a pallbearer. But he’s as hale and hearty as you, and: he went to the Citadel; he’s lived the Code; he will not be denied. He jumps in with the rest and you’re damn glad he does. Together, the seven of you carry the flag-covered casket to the awaiting grave.

You glue your eyes to the spectacle before you; it’s a dream, and dreamlike, it will evaporate before you know it. You labor to take it all in and remember, remember . . . You round a corner and it’s out of sight for a bit; you round another corner, this time almost to the gravesite, and it’s still there, all of it. You get out of the car and mill around for a bit. Everyone’s crying as they look at the magnificent sight of the Marines, some of them surely the same age as your dad, when he was in the Corps. You and the other pallbearers line up at the back of the hearse. Suddenly, your dad’s brother-in-law Bob (Jane’s husband) joins us. He’s an “oldster” – just turned eighty – and in following the FD’s advice (yet another of your many oversights and mistakes in this whole process) you didn’t have him as a pallbearer. But he’s as hale and hearty as you, and: he went to the Citadel; he’s lived the Code; he will not be denied. He jumps in with the rest and you’re damn glad he does. Together, the seven of you carry the flag-covered casket to the awaiting grave.

You sit next to your mother on the front row. Everyone assembles behind you. You hear a gentle tapping on the tent; it’s

started raining. In thirty seconds, it’s

over. Someone from the funeral home touches

your mom’s shoulder: “I’ll let you know when they’re going to fire the guns, so

you’re not startled.” A few moments

later you hear the crisp click of the weapons and three shots are fired in

unison. Then, hauntingly, lovingly,

gently, “Taps” begins to echo through the pines and over the hills, one last

time dad, for you.

And you’re so caught up in it, tears streaming,

straining to take in the fullness of every note, marveling at the casket and

the two Marines at either end of it now, holding up the flag preparing it for

the folding ceremony, that you forget to do the one thing you’d promised

yourself you’d do at that moment: stand up and salute your father one last

time. Jesus, how could you forget

. . .?

Then the two Marines standing straight and tall holding

the flag – one black, thin as one of the pines, looking impossibly young; one

white, older, stockier, who could have been my dad sixty years ago – begin the

folding: studied, meticulous, detailed, deliberate, painstaking. Upon finishing, the stocky one kneels down in

front of your mother and says: “On behalf of the President of the United

States, the Commandant of the United States Marine Corps, and a grateful

Nation, please accept this flag as a symbol of our appreciation of your husband’s

service to Country and Corps.” Tears

upon tears upon tears.

And it was over. All over, suddenly.

You stand up and try to come back to reality. People begin to talk and walk back to their

cars. You head straight to the two vans

that the Marines came in and thank them for what they just did for you and your

mother and your father. Months ago you’d

told your father you were going to send him off this way. He gave you a wry look, which was to say: “Yeah,

too bad I won’t be around for it.” You

said, “Yeah, I know, but I wanted to tell you; I wanted you to know.”

It's just a box of rain

I don't know who put it there

Believe if you need it

Or leave it if you dare

But it's just a box of rain

Or a ribbon for your hair

Such a long long time to be gone

And short time to be there

-- Robert Hunter

It's just a box of rain

I don't know who put it there

Believe if you need it

Or leave it if you dare

But it's just a box of rain

Or a ribbon for your hair

Such a long long time to be gone

And short time to be there

-- Robert Hunter

he's gone . . . cont'd

The three of you reassemble downstairs and you all start

making your to-do list:

Call Jean Hurlburt (the wife of your dad’s oldest

brother)

Program for funeral

Get in touch with minister

Talk to Jane (your mother’s sister) about remembrance

“Because He Lives” (song your mother wants sung at

the funeral)

Pallbearers

Eulogy

Etc. You discuss/talk/make lists for a couple of hours

until finally, exhaustion. You give your

mom a hug and kiss and say something comforting (you hope . . . you can’t even

remember what you said) and go home.

You can’t remember if you cried on the way home,

but you must have. You open the door to

your house for the first time having no father.

You catch yourself thinking that you’re doing everything now for the

first time since your dad died. You can’t

remember if you took a Xanax to go to sleep, but you probably did.

Tuesday:

You awake with a thousand things to do. You attack the list from last night; you

assume Sandie and your mom are attacking theirs. You work like a madman on the eulogy. You’d made some notes conceptualizing how you

wanted it to go . . . but now it’s real life and it has to be right, it

has to honor him, it has to live up to him. You do . . . a thousand things in a blur (and

today, writing this, you can’t remember ten of them). Where did you eat? When did you go to bed? How many words did you write? How many times did you rehearse “Brokedown Palace” (the song

you and Rebecca and Jenny will sing at the funeral)? Who did you call? How is you mother? You have no idea.

Wednesday:

You finally get in touch with Holmes (he was out of

town yesterday) and get the program together.

The front and back covers are paintings your dad had done over forty

years ago. Holmes, no slouch of an

artist himself, said, “Wow, these are really good.” They are, and you have several others, but

you wish he would have painted more. Painting

– a silent, solitary pursuit – suited him.

(Note to self: get your art – writing, music, photography, whatever –

done now, because one day you can’t.)

On the inside-left page you’ve placed Philippians

4:8 (“Finally brethren, whatsoever things are true, whatsoever things are

honest, whatsoever things are just, whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things

are lovely, whatsoever things are of good report; if there be any virtue, and

if there be any praise, think on these things.”). Christopher Hitchens used this verse at his

father’s funeral “because of its non-religious yet high moral character,” and

he goes on to say: “Try looking that [verse] up in a “modern” version of the

New Testament and see what a ration of bland doggerel you get. I shall never understand how the keepers and

trustees of the King James Version threw away such a treasure. But that very thought, if you like, is partly

taken from my father’s legacy of suspicion of change and of resistance to the rude

shock of the new.” To which you say:

Amen. On the inside-right is the order of

service.

Rebecca comes over to rehearse a bit; she’ll pick

up the programs from Staples later. You

write solidly throughout the day. You’re

on the phone a lot. You’ll never get

everything done, you think, and you wish the funeral was Friday.

Rebecca calls around dinner time from Staples. “What’s my name?” she says. Uh . . . Rebecca? you say, wondering

where this unique line of questioning is going.

“What’s my last name?” she says.

Well, this one’s easy; but you say, uneasily, and with that question

mark at the end: Hurlburt? You

still don’t know what she’s getting at. “Dad,”

she says, “I’m married, my last name is Causey.” Shit.

On the program you listed her as Rebecca Hurlburt, not Causey. Way to go, D.

At least we laughed about it.

Rebecca brings over dinner and the programs. Jenny’s supposed to be in from NYC around

8:00 to rehearse. Her plane is delayed

and then she has to change planes and that’s delayed and she ends up getting in

at midnight. (In the process, she leaves

the funeral remarks she’d been working on on the first plane. She’s up til three rewriting them.) You run through the song a few times with

Reba. You hammer away on the eulogy.

Thursday:

An invisible sun rises and the morning comes muggy

and grey with the promise of rain. It came in darkness for you.

After waking up at one, two and then four o’clock, you finally decide to just

get up. The eulogy you’ve been working on for two days could still use

some polishing; you’ll deliver it one-time-only, about six hours from

now. It better be good.

The girls come over before eight; you sing “Brokedown

Palace” a few times. Phillip shows

up. You assemble everything – eulogy,

chord/lyric sheet, guitar, guitar stand, music stand, phone, etc. – and hope/pray

you haven’t forgotten something.

more to come . . .

more to come . . .

Friday, September 7, 2012

he's gone

It’s been a long time coming . . .

It’s gonna be a long time gone.

-- David Crosby

Today, Friday, the weight has lifted; heaviness

remains.

The heaviness is a black hole who’s infinite mass

makes the concept of “weight” seem slightly . . . daft.

Yesterday:

An invisible sun rises and the morning comes muggy

and grey with the promise of rain. It

came in darkness for you. After waking

up at one, two and then four o’clock, you finally decide to just get up. The eulogy you’ve been working on for two

days could still use some polishing; you’ll deliver it one-time-only, about six

hours from now. It better be good.

Monday:

Your father, Stewart Albert Hurlburt, died tonight

in his home of twenty years at 7:45 as you, your mother, and his (still)

daughter-in-law sat outside on the deck ten feet below him, finishing dinner

and talking about . . . what? Nothing

really. The nurse appears; from the

corner of your eye you see her walk into the living room. She’s been sitting with your dad and there’s

no reason for her to come downstairs except . . .

She says, haltingly, that we all might want to go up

to his room.

Don’t believe the line: “He died peacefully in his

sleep.” Bullshit. “Peace” is not: the Bastard Death eating

flesh, organs, heart, memory and soul (make no mistake: it devours the soul) away until you die. Yes – his eyes are closed, he’s in bed, he’s

not thrashing about – but, “sleeping?” Really?

Peace and sleep are relatively grotesque, lame euphemisms that have nothing to

do with it.

You’d rather say he died with a certain symmetry and

order (concepts he loved): the first

heart attack was Labor Day, 2010; he died Labor Day, 2012. Dying, of course, is not easy; it is work,

hard work. Labor.

There are tears – not wracking and slobbering, you’ve

already done that a few times – but gentle and resigned and relieved and sad

and . . . glad? He’s gone; he’d suffered

too damn long. You’re happy?

Not exactly, but still . . .

His head is turned to one side, the mouth open –

just one last breath. You put your hand

on his still-warm chest; it has a heart but no beat. Nothing covers his ribs but a raged t-shirt

and skin; his flesh was not weak, it was gone.

“Skin and bones.” You idiotically think of Sally Struthers and starving

Biafran children. Jesus, what is wrong with

you?

Your mom dabs tears; she lets out a small groan – an

ancient, primitive, guttural, involuntary ache.

She puts her hand on his forehead.

She (and Sandie and you) looks at what used to be Him. “Awww . . .”

So much heartache in one small utterance. Her first word as a member of that horrible

sisterhood: The Widows.

You sit in the chair beside the hospital bed (the

one he’d slept in for twenty years had been replaced several days ago). You get up, walk into the hallway. You come back in the room and sit in the

chair and stare. You get up, back into

that same damn hallway. You return to

the same damn chair. What the hell are you doing?

The minutes tick by at the raw beginning of this

first-day-of-the-rest-of-your-life.

Utility and pragmatism unexpectedly kick in. The nurse has called the hospice people;

someone will come to record the death.

She asks us to leave the room so she can make Stew presentable, i.e.,

straighten out his head, cross his arms nicely across his waist, make the

sheets neat and just so.

The necessities.

You start calling people: Rebecca and Jenny (your daughters), Jane (your mother’s

sister). You text friends. You think to post on Facebook but don’t. You haven’t been able to reach Jenny and you

don’t want her to find out that way.

The nurse tells us it’s OK to go back in the room. The mouth is still “oh” agape. My mother tries closing it; it resists.

Then a blur. You go downstairs. You gently cry. You hug each other. What else?

At some point you get pen and paper and start to make a to-do list. You wait for Rebecca to arrive in case she

wants to see the body. She arrives and

says no, she doesn’t. Does the hospice

rep arrive before or after Rebecca? You

can’t remember.

The hospice rep calls the funeral home. Soon an Unmarked Black Van arrives. (You idiotically think of Mission

Impossible – not the jacked-up movie, but the great TV show you watched

religiously with your brother in happier family days). You open the door and see two young guys – one

black, one white – getting out of the van, the white one still getting dressed

for the occasion: he’s trying to attach a clip-on bow tie. My mother tells him not to worry, but he puts

it on anyway. With their standard-issue and somewhat ill-fitting Men in Black

suits, shoes and ties, they could pass for Mormons making one last house call,

doing mission work.

Polite to a fault, they shake your hand and look you in the eye. They’re sorry for your loss. They convey sincere sincerity and pastoral corporate

compassion. They are on a mission. They’re

impossibly young, and their job is to ferry old, dead people back and

forth. Jesus.

Jesus.

They bring in a stretcher, which is impossibly . . .

narrow. In the span of a week, your dad has gone from his own four posted double bed to a hastily assembled single-size hospital

bed to this stretcher that’s barely a foot wide. Well, at least you know he’ll fit on

it easily and they won’t have any trouble carrying it to the van.

more to come . . .

more to come . . .

Monday, September 3, 2012

going going . . .

Your dad had his first heart attack Labor Day, two years ago. No one thought he would make the next one, much less the second.

Today is his second Labor Day since that heart attack. Instead of weighing 160, he weighs 100 pounds. He's not left his bed in a week; he doesn't eat; drinks little. He exists at this point; he doesn't live.

Your mother's worrying herself sick, trying to do something, anything, where nothing can be done.

You were at Rebecca's yesterday sorting through hundreds of photos of him, your mother, your brother, you. We put 118 of them in a slide show for the funeral.

You wrote this two years ago:

Today is his second Labor Day since that heart attack. Instead of weighing 160, he weighs 100 pounds. He's not left his bed in a week; he doesn't eat; drinks little. He exists at this point; he doesn't live.

Your mother's worrying herself sick, trying to do something, anything, where nothing can be done.

You were at Rebecca's yesterday sorting through hundreds of photos of him, your mother, your brother, you. We put 118 of them in a slide show for the funeral.

You wrote this two years ago:

Lunchtime: Got a call from Sandie, who -- with Jenny, Rebecca

and Philip – was visiting my parents at their house in Highlands for

Labor Day. She said that my dad had gone to the emergency room the day

before for some coughing/complications with pneumonia (with which he had been

diagnosed a week earlier by Dr. (?) Bergeron), had been examined and

prescribed some medicine to help with some swelling in his ankles, and because

he said he felt better and wanted to go home --they let him. She said

he didn’t look too good.

I decided to go to Highlands. No one would be there after

Labor Day; my mother was exhausted from the ordeal; what if something happened

and no one could help her?; this was serious. I’d never driven from WB to

Highlands: should I drive straight there? Should I stop in Atlanta

first? Could I fly? What’s the nearest airport? How long is it

driving vs. flying. How much does it cost to fly? Etc.

Decided the best was was to drive WB > Highlands. It would

take 7+ hours.

I threw stuff together and was on the road by two, in Highlands by

9 p.m.

Dad, sucking it up, and, always trying to do the "right

thing,” came out to greet me (in his bathrobe) when he saw me pull into the

driveway. My mother ran behind him, yelling, “Stewart, don’t be STUPID

going out in the wet weather. Get back inside – it’s STUPID to be out here

. . . what are you doing?! And I’m thinking, Jesus, Mom, if he’s

about to die, could you just not call him "stupid" . . .?

Monday –

After lunch dad comes out of his room after an aborted nap, looking stricken. He says he doesn’t feel good – at all. We go immediately to the emergency room, where they finally do a bunch of heart tests on him. (For some reason, he told the doctors the time before he didn’t have a history of heart problems . . . ) He’s immediately put on a heart drug and continues with the diuretic. He’s feeble, weak and not looking good. His heart has half the capacity to pump blood as a normal heart, and that’s only going to decrease with age. The doctor speaks to me and mom outside my dad’s hearing and tells us this is REALLY SERIOUS, THAT HE MIGHT NOT MAKE IT.

REALLY. That he should have been on this medicine months, if not years, ago.

After lunch dad comes out of his room after an aborted nap, looking stricken. He says he doesn’t feel good – at all. We go immediately to the emergency room, where they finally do a bunch of heart tests on him. (For some reason, he told the doctors the time before he didn’t have a history of heart problems . . . ) He’s immediately put on a heart drug and continues with the diuretic. He’s feeble, weak and not looking good. His heart has half the capacity to pump blood as a normal heart, and that’s only going to decrease with age. The doctor speaks to me and mom outside my dad’s hearing and tells us this is REALLY SERIOUS, THAT HE MIGHT NOT MAKE IT.

REALLY. That he should have been on this medicine months, if not years, ago.

Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday –

When the doc is doing his rounds in the morning, he says both times how surprised he is (again)that dad wasn’t on Lisinopril because it’s SOP to use it in people with weak hearts. The doc said that he uses it every day, and looked at me to indicate I might want to think about doing it. It is a minimal-side-effect way to allow your heart to work more efficiently.

When the doc is doing his rounds in the morning, he says both times how surprised he is (again)that dad wasn’t on Lisinopril because it’s SOP to use it in people with weak hearts. The doc said that he uses it every day, and looked at me to indicate I might want to think about doing it. It is a minimal-side-effect way to allow your heart to work more efficiently.

Stew improves remarkably (even the doc says this) as the drugs

begin to work.

Pamella, Rebecca and Philip come up Tuesday. Jenny Wednesday,

Sandie late Wednesday night. Pamella the kids and I got out for dinner

Wednesday at Paoleti's. Food is average, but the drive in to

Highlands, with Reba, Jenny and Philip acting apeshit to a Phish CD I brought

along was hilarious.

Sandie, Pamella and I had dinner with Jane (my mother’s sister) at

Wolfgang’s Thursday. (Mom stayed at the hospital with dad.)

Jane telling stories about Barb growing up; how horrible her dad was; how

he (mis)treated his wife (“a slave”) and daughter; how Barb told Emma

Laura when Jane became a teenager “not to let daddy do to her what he did to

me.” I knew he (my grandfather) was tough, but not that he was an actual,

full-bore woman-hater. My mother was the first child (of four), and a

girl, and received the brunt of his craziness.

Friday –

Dad is actually well enough to go home. The drugs are allowing/ maximizing his weakened heart’s ability to pump as much blood through the body and organs as possible. The drugs will not increase the lifespan of the heart muscle; they will improve the quality of the life he has left. The doc says Stew’s a remarkable guy. He is, and I don’t know if he knows how close he came to dying.

Dad is actually well enough to go home. The drugs are allowing/ maximizing his weakened heart’s ability to pump as much blood through the body and organs as possible. The drugs will not increase the lifespan of the heart muscle; they will improve the quality of the life he has left. The doc says Stew’s a remarkable guy. He is, and I don’t know if he knows how close he came to dying.

Saturday, Sept. 11--

Sandie and mom went to Atlanta for the day. Barb is to come back this evening with Pamella; Sandie tomorrow evening by herself.

Sandie and mom went to Atlanta for the day. Barb is to come back this evening with Pamella; Sandie tomorrow evening by herself.

Out of nowhere, sitting at the counter eating a BLT I fixed him,

as animated as I’ve seen him since I’ve been here – dad looked at me and

said: “Can you believe Jane going out there and telling the Pike's about

me being in the hospital? Why is it she had to inject herself into everything?! It’s none of

her business, and she has no business telling anyone about what’s going on with

me.” I asked how it would hurt that the Pike's (dad’s and mom’s “best

friends” in Highlands) knew about his illness. He said that if the Pike's

knew, that pretty soon “it would be all over the club” (i.e., that the members

of the Cullasaja Club would know). I asked dad specifically why he

and mom didn’t want "the club to know." I mean, so the-fuck

what? Who cares? He said he didn’t want them to think

they were “big sticks [I think he meant “big shots”] or something. We’re

just not comfortable with that.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)